If you love gardening it can be really tough to stay in the moment and enjoy winter. It’s much easier to look at seed catalogs, dream of next season’s garden, and mope that it’s still too cold to go plant peas. But winter is actually a great season too. It’s a good time to relax, reflect, and learn.

Visit an Agricultural Event

There’s many agricultural events that go on across the country each winter. Most offer awesome workshops or classes that can really help you become a better gardener. Plus they’re great places to network. Especially if your event is local you can make friends with people who share your passion for gardening and learn about their ideas.

Southern Exposure attends a variety of events over the winter like the PASA Farming for the Future Conference or the Mother Earth News Fair. Be sure to check out SESE’s Event Schedule.

Read a Gardening Book

Curling up by the wood stove and reading a good book is a classic winter pastime. It’s easy to reach for that new novel from your favorite author but this winter make sure you grab a couple nonfiction gardening books too. You can find a lot of great, educational books in Southern Exposure’s store that are sure to up your gardening game. You can find the book section here.

Subscribe to a Gardening Blog

We’re may be a little biased but we think SESE’s blog is pretty awesome and you can sign up for our newsletter to get notified when there’s new content to check out. There’s a lot of other great, informative blogs out there though. Some of our favorites include Mother Earth News, Rodale’s Organic Life, and Modern Farmer but there’s a lot more great ones out there especially if you’re looking for a specific niche.

Go Through Your Garden Journal or Get One Set Up

Keeping a garden journal is a great way to learn all on your own. Plus its the only educational material that’s focused on your actual property. Getting advice from other sources is great but no two properties are exactly alike. If you have a garden journal from last year set aside some time this winter to go through it and check out what worked well and what needs improvement. Maybe make some resolutions for the coming year.

If you haven’t started a garden journal set one up for the coming year. You’ll probably be more likely to use it and get more out of it if it’s well organized. Consider setting up sections for planting dates, notes on specific varieties, weather conditions, and more. You can also surf the web for free or cheap garden journal printables if you need some ideas.

Take an Online Class

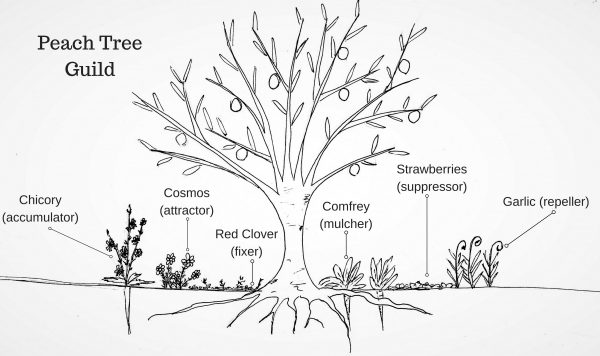

There’s a surprising amount of online courses available for gardening related topics and many are cheap or free. Find something that suites your interest like a class about herbalism, permaculture, or even short, simple classes like how to set up drip irrigation.

Watch a Few Videos

While spending all winter in front of the TV or computer isn’t a great idea if you like to watch anyway maybe you can swap some of your viewing time for educational movies or shows. SESE has a few DVDs available or browse Youtube for some great free options.

Just because winter is an off season for many gardeners doesn’t mean you can’t still be working towards the garden of your dreams. Spending time learning this winter will help you to beat the winter blues and get a better harvest next year.

Pin it for later.