As most of you probably know, we’ve been inundated with orders this last month. We’re thrilled that folks are looking to our seeds during this challenging time but we’ve also had trouble keeping up. We’ve had to suspend taking new orders several times now while working to get seeds packed and shipped. We thought this would be an appropriate time to take a look behind the scenes at Southern Exposure.

The graph below compares the number of daily orders for some days in March and April from 2013 to 2020. Not shown in this graph is that we also saw an increase in order size. Folks that maybe would normally purchase just a few packets ordered more packets and larger packets (bulk sizes) this year.

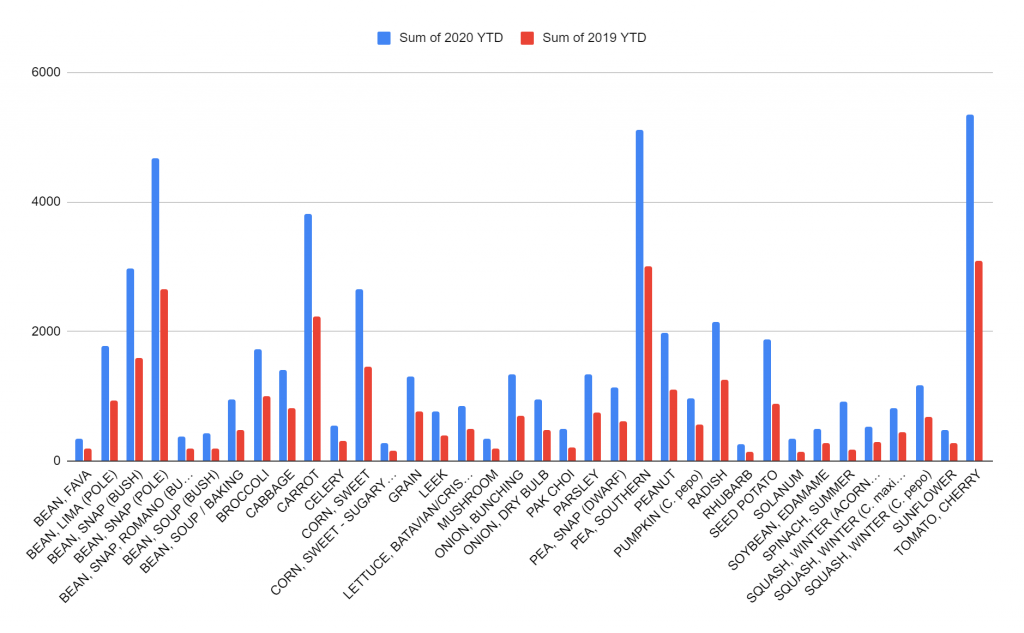

The graph below compares some of the 2019 and 2020 sales by category.

Our Network of Growers of Small Growers

Did you know SESE gets approximately half of our seeds from our network of small growers? These are the seeds you see marked with a purple “S” on our website and in our catalog.

That’s a really high percentage of seeds! Most larger seed companies buy most of their seeds from wholesalers – it’s a ton of work to fill all the seed orders that come in, and directly contracting with seed growers adds a lot of extra work on top of all that order fulfillment.

Each year about 60 small farms grow seed for us. Most are family farms with few if any employees. Some grow as little as one variety while others grow as many as 40.

Before each growing season, we make a list of seeds we need and send it out to our growers. We include a price per pound or ounce of seed and a range of how many pounds/ounces we’d like. The lower end of this range is estimated to be about 1 year worth of seed and the higher side is about 2.5 to 3 years of seed. The range may be different depending upon the crop type and how well it stores.

Almost all of our farmers, aim for the high end of the range. Different varieties need to be isolated from one another, so it benefits farmers to get the most they can out of each isolation plot. For the most part, we provide the option for growing one year of seed to avoid penalizing farmers who have a bad crop due to pests or weather.

Small Growers and the Pandemic

As far as the pandemic is concerned, we see a few benefits from our network of small growers. The first is that we purchase more than 1 year of seed. This helps us be prepared for years like this year when we received more and larger orders than expected. Also, on small family farms with few employees, we don’t see workers crowded into tight conditions that you see with larger industrial-scale operations.

However, many of our seed growers are older folks who would be considered at relatively high risk of experiencing serious side effects from COVID 19. We love our seed growers and are hoping they all have a healthy, happy, and successful growing season.

Wholesale Seed

We also purchase wholesale seed. These seeds don’t have the purple “S” in our catalog and on our website that seeds from small growers do.

We strive to work with companies that value organic agriculture as we do. Terra Organics, Seven Springs Farm, and A. P. Whaley Seeds are great examples of our wholesale sources.

Seed Storage

Partially because of the quantity of seed we purchase at a time, we have a lot of seed storage. We keep our seeds in a walk-in freezer and climate-controlled storage room.

Seeds can remain viable for many years if properly harvested and stored. As we only want to provide our customers with quality seed with high germination rates, we only store for a few years at a time and test our seed each year.

What does the future bring?

- If sustained, our unusually high sales mean that we might sell out of half of the varieties grown by our small growers. First, we’d run out of seed grown and then shipped to us in the fall of 2018, which we sold in 2019 and 2020. The seed grown in 2019 is expected to last through 2020 and 2021.

- We expect our wholesale seeds already on hand to last until the fall of 2020 (some until late 2021).

- We may sell out of certain varieties but we won’t sell out of whole crops.

- Beans and southern peas were most affected by the sales surge. Pole beans in particular are difficult for growers because they require trellising which involves extra work and expense.

- We had a few crops that were removed from the 2020 catalog due to lower sales that may be back for 2021 if we run out of other varieties.

- We’ll be asking our growers if they’re interested in increasing their production by 10% this year.

- You might see a change in the size of our seed packets to make things easier on our supplier, Cambridge-Pacific.

While not all of our seeds come from small growers, we feel supporting these farms goes a long way to making our company more sustainable and resilient. Thanks to all of our customers for joining us in supporting family farms each year.