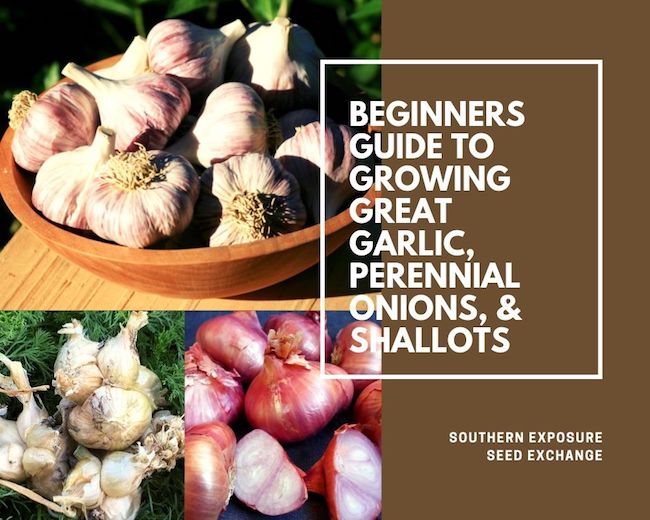

It’s that time of year again! The arrival of cooler temperatures and changing leaves means it’s time to add perennial onions and garlic to your garden. Both of these are great crops because they provide tons of flavor, take up little space, and you only have to buy them once. Both are easy to cultivate for years.

Choosing a Variety

The most important thing is to get quality seed. While you can purchase garlic at the grocery store it won’t do as well as garlic from a reputable source. Store-bought garlic is often treated so that it won’t sprout and may be adapted to growing in a climate different than your own.

Perennial Onions & Shallots

At SESE we carry a variety of perennial onions including shallots, Egyptian walking onions, multiplier onions, and potato onions. Egyptian walking onions are topsetting onions that are typically used for their hardy greens. Shallots, multiplier, and potato onions are planted as single bulbs and produce multiple bulbs which can be harvested or divided and replanted the following summer.

Garlic

At SESE we carry four types of garlic; hardneck, softneck, Asiatic & turban, and elephant garlic.

Hardneck or rocambole garlic is better adapted to cooler climates and performs best from Virginia northward. It has become more popular recently because it produces flower stalks or scapes that can be cut and eaten before the garlic is ready to harvest. Hardneck garlic varieties have a diverse range of flavors.

On the other hand, softneck garlic does best in warmer climates and is more domesticated than hardneck garlic. It doesn’t produce scapes. However, the lack of scapes makes it easy to braid softneck garlic. It also stores incredibly well and typically has higher yields.

Asiatic and Asiatic Turban garlic are tentatively identified as an artichoke subtype. Unlike most artichokes types, the stems are hardneck; however, in warm climates, they may revert to softneck.

Though elephant garlic isn’t true garlic it is cultivated in the same way. It has a milder flavor than other garlic making it perfect for raw use. It’s also excellent steamed with other vegetables.

Planting

The first step to planting garlic and perennial onions is selecting an appropriate planting site. Although you plant in the fall, you need to consider what your garden is like in the summer. Garlic and perennial onions both produce the best bulbs with full sun. They also need lots of organic matter, neutral pH, and good fertility. Amending your bed with good quality compost and using a broad fork to loosen the soil is an excellent idea. Compost adds both fertility and organic matter and can be used to improve any soil type whether you have sandy beds or heavy clay. Raised beds are also ideal.

To plant garlic, gently separate the cloves and plant them tip-up, 6 inches apart or 10-12 inches apart for elephant garlic. In southern climates, they should be covered with about 1 1/2 inches of soil and in northern climates about 3-4 inches of soil.

Large perennial onion bulbs (3–4 in. diameter) should be planted 6–8 in. apart while smaller bulbs (½–2 in. diameter) can be planted 4–6 in. apart. White multiplier onions and perennial leeks should be spaced 2 in. apart in rows 12 in. apart. Space Egyptian walking onions 9 in. apart.

No matter what variety you’re planting we recommend planting in rows for easy of cultivation. To get good-sized bulbs both perennial onions and garlic should be kept as weed-free as possible.

Care

Perennial onions and garlic both benefit from a thick layer of mulch. This helps to suppress weeds, keep them moist, and protect them from the cold, especially while they’re getting established during the fall. Leaves, straw, hay, grass clippings, and woodchips can all be used to mulch onions and garlic.

Adequate watering is important for a productive crop. Keep your soil moist as onions and garlic are getting established during the fall and while they’re growing in the summer. Watering should be stopped two weeks before harvest to allow the skins to dry and harden. All alliums should be kept as weed-free as possible.

Harvesting & Curing

Harvesting garlic and perennial onions isn’t as simple as tugging them out of the ground. In order to store well, garlic and perennial onions both require proper harvest and curing. Before harvesting onions the tops should turn brown and fall over. Garlic should be harvested when the lower ⅓ of the leaves turn brown.

Try to avoid breaking stems. Unless your soil is very loose you may want to use a garden fork to harvest onions and garlic as gently as possible. For hardneck garlic, scapes are best harvested when they’re mild and tender. Remove scapes by clipping them off at the base before the ends curl.

To cure onion and garlic bulbs lay them out in a single layer on wire screens or wooden shelves in a well ventilated, dark spot for 1-2 months. Curing improves their flavor and storage ability.

For more information visit our harvest and curing guide.

Want to pick up onions and garlic in person? Be sure to visit us this weekend at the Heritage Harvest Festival!

Additional Resources

- Perennial Onion Cultural Notes

- Garlic and Perennial Onion Growing Guide

- Incredible Perennial Onions (history & benefits)

- Time to Order Garlic and Perennial Onions: How to Pick Which to Grow in Your Garden

- Garlic and Perennial (Multiplier) Onions: Harvest and Curing

- Winter Storage: Garlic & Perennial Onion Bulbs