January may be the depth of winter, but it’s also when we begin starting seeds indoors for the coming season. Whether you’re new to gardening or just new to starting your own transplants, these are the seeds we recommend starting indoors over the winter and how to have success with them.

At Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, we’re in USDA zone 7a. For northern gardens, or those much farther south, your ideal planting dates may be later than ours or even earlier. For exact planting dates based on your zip code, try our garden planner app.

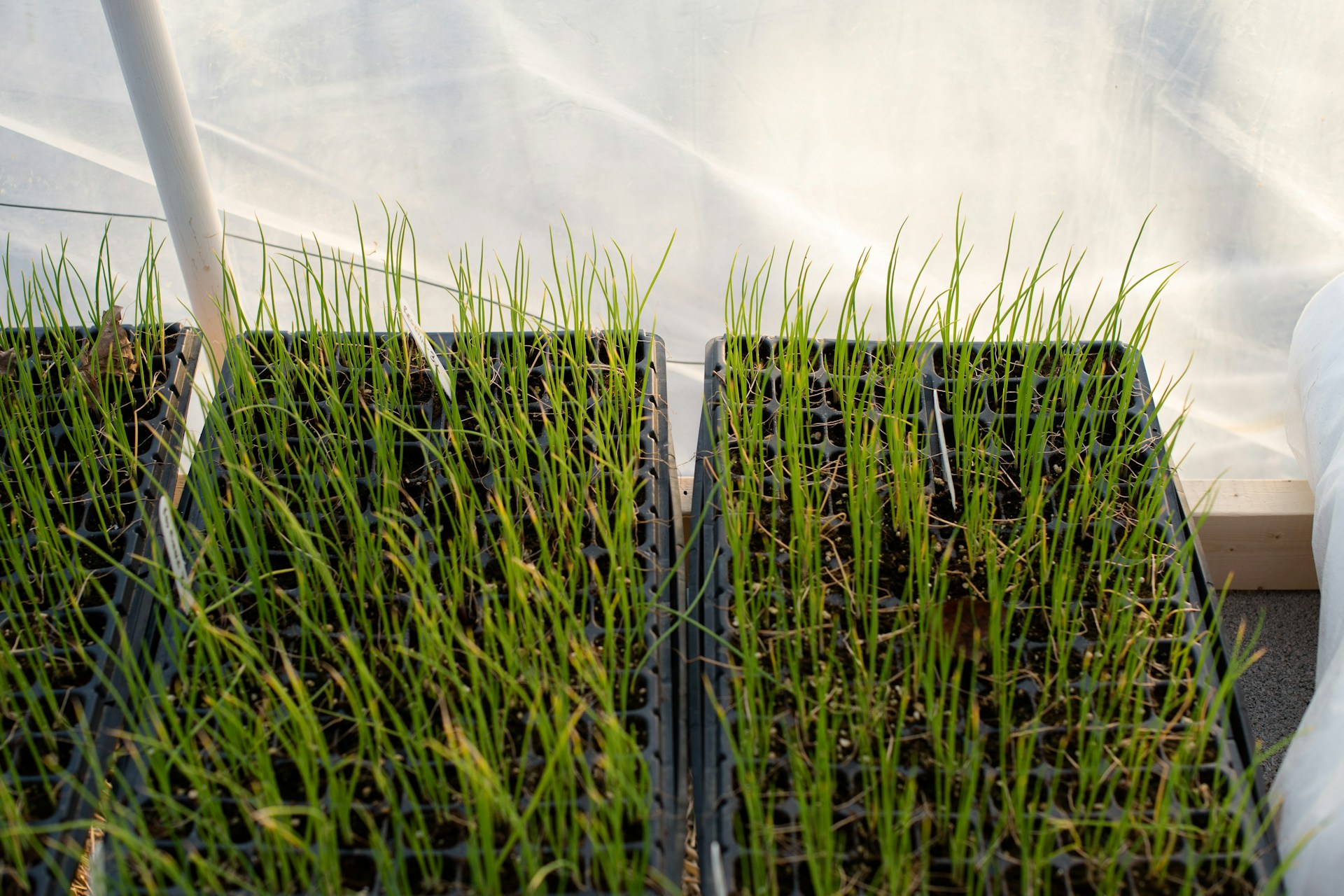

Bulb Onions

The earlier you start onions, the better! To bulb up nicely, these plants need plenty of time to grow. In fact, we often sow them in cold frames as early as November. If that’s not an option, we recommend starting them indoors in January.

Cabbages

Cabbages are a wonderful, hardy spring crop. If you want cabbage quickly, focus on early varieties like Early Jersey Wakefield. We sow successions of cabbages for months, starting January 31st. Sow your first cabbages about 4 to 6 weeks before you plan to transplant them.

For best germination, keep the soil temperature at about 75°F. You can reduce it to 60°F once your plants have germinated. For strong transplants, cabbages need strong, direct light and should be potted up as needed.

Maintain good air circulation around plants during all growth stages. Harden plants before transplanting, starting a month before the last frost. When plants have become properly hardened, they can stand a temperature as low as 20°F without buttoning up.

Broccoli

Broccoli thrives in the spring’s cool temperatures, so it’s a good idea to get your seedlings started on time. We begin sowing broccoli indoors on January 31st or about 4 to 5 weeks before transplanting out.

You can transplant broccoli about a month before your last frost, but don’t transplant too early! If seedlings experience 20°F or lower, they may “button up” and only make tiny heads.

Cauliflower

Similar to broccoli, we begin sowing cauliflower indoors on January 31st. You can sow them about 4 to 7 weeks before your last frost so that they’re ready to transplant 2 to 3 weeks before that date.

Celery & Celeriac

In Virginia, we sow celery and celeriac in between January 21st and February 15th. Both plants germinate slowly in about 14 to 21 days at temperatures between 65 and 75°F. For best results, use a sterile seed starting mix and sow the seeds no deeper than 1/8 of inch.

Celery and celeriac perform best in areas free of temperature extremes so they can be a bit tricky here in Virginia where the summers get hot. We try to get them out early and use a thick mulch to keep the soil cool.

Brussels Sprout

While Brussels sprouts are quite cold hardy, we don’t actually start these plants until late spring, between May and June. Brussels sprouts have a long season, and we grow them for a fall harvest.

Sow seed 1/4 to 1/2 inch deep in deep flats or pots. Transplant them out to the garden as soon as they develop several sets of leaves.

Tomatoes

Sow tomato seeds indoors starting about 6 weeks before your last frost. We sow our tomatoes between February 21st and May 7th. Sow seeds about 1/4 inch deep in shallow flats. Tomatoes are warm weather loving plants and germinate best when you maintain a soil temperature between 75° and 85°F.

When the seedlings have produced several leaves, transplant to 3-inch pots to promote root growth. After transplanting, keep seedlings at a lower temperature at night, 50° to 60°F, to promote earlier flowering in some varieties. Day temperatures should rise to 75° to 85°F. to promote rapid growth.

To develop hardy seedlings, expose your tomatoes to air currents and plenty of light. Water them sparingly, but don’t allow their growth to be checked by too little water. If you notice the leaves becoming yellow or purple, use a soluble fertilizer, fish emulsion, or liquid kelp to fertilize the plants. They need high levels of phosphorus, but too much nitrogen can delay fruiting.

Don’t transplant your tomatoes out until your garden soil temperatures have reached 60 to 65°F.

Ground Cherries

See the tomato guide above.

Tomatillos

See the tomato guide above.

Peppers

Sow peppers indoors 8 to 10 weeks before your last frost date. Plant the seeds about 1/4 inch deep in shallow flats. Like tomatoes, they need warm soil, between 75° and 85°F. In peppers, soil temperature makes an enormous difference in germination time! In warm soil, pepper seeds typically germinate in about 5 days, but in cool soil, they may need up to 20 days to germinate.

Peppers don’t like soggy soil. Avoid over-watering or they may rot. Water them with warm water to keep the soil moist but not drenched.

Pepper production is also greatly reduced if the plants become crowded or rootbound. When plants develop several leaves, transplant them into 3-inch pots. Pot them up again as needed until you’re ready to transplant them outside.

Don’t rush to transplant! You must harden peppers off carefully. Set them outdoors for a few hours on warm days, being careful not to let them wilt. Transplant your peppers outdoors after the dogwood blossoms have fallen and when the average soil temperature is 65°F or above (usually a month after the last frost).

Eggplants

Eggplants have very similar requirements to peppers (see the above section). Start them indoors about 8 to 10 weeks before your last frost. They need warm, moist soil to germinate well.

Wait until 1 to 2 weeks after your last frost to transplant your seedlings. Don’t rush to transplant. Cold weather will shock eggplant seedlings and reduce production.

Optional

- Lettuce

- Cucumbers*

- Collards

- Kale

- Watermelon*

- Marigolds

- Zinnias

- Cosmos

- Basil

*All the starred crops are members of the cucurbit family. Cucurbits have delicate root systems. If you choose to sow them indoors, it’s best to use paper or peat pots so that you can transplant them without disturbing the roots.