Everyone wants to find presents that make their friends and family feel understood, appreciated, and loved. Thankfully for anyone who like gardening or wants to learn there’s plenty of easy, affordable, and sustainable gift ideas to excite any gardener this holiday season.

Many of these ideas are also great whole family gift ideas for those with kids. Gardening focused gifts can help children get excited and involved in the outdoors with their family.

Check out some of SESE’s awesome popcorn varieties like the rainbow Cherokee Long Ear Small Popcorn (pictured above) or Pennsylvania Butter-Flavored Popcorn for a truly gardener twist on the classic “movie night” basket. For the ulimate experience check in during harvest time and bring over your favorite gardening documentary.

Know a gardener or budding permaculturalist looking to branch out? You can order mushroom spawn from Sharondale Farm through SESE. It’s an excellent gift for those looking to add productivity to shady areas of a property.

DIY Insect Hotel, Bird, or Bat House

Handmade gifts can be especially meaningful. Making an insect hotel, bird, or bat house will help you show off your DIY skills, improve your loved one’s garden, and give some deserving species a helping hand.

CobraHead ‘Steel Fingernail’ Weeder and Cultivator

This is one of Southern Exposure’s favorite tools for small gardens. National Garden Club testers were really impressed with it as well. Plus it’s made in the USA.

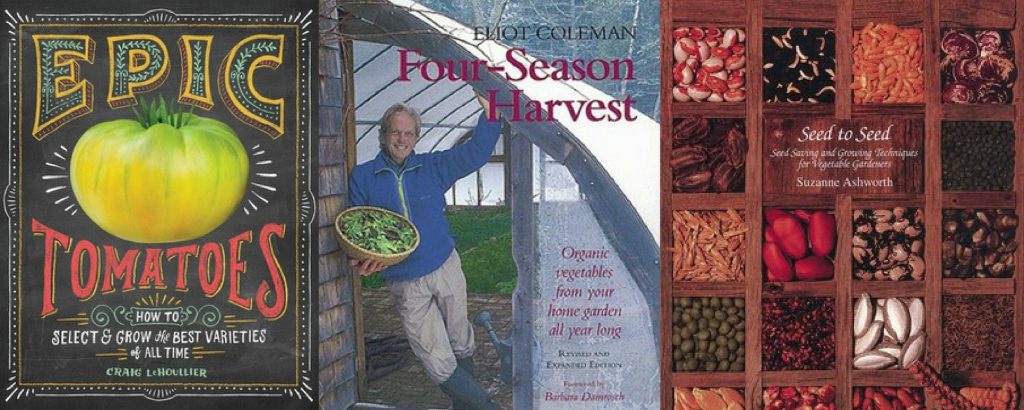

SESE is known for selling seeds but we also offer some great DVDs and books for any gardener to expand their knowledge and gather more inspirational project ideas. Some of our favorites include:

- The Resilient Gardener by Carol Deppe

- Epic Tomatoes: How to Select and Grow the Best Varieties by Craig LeHoullier

- Vegetable Gardening in the Southeast by SESE’s own Ira Wallace

- Wild Fermentation by Sandor Katz

- SEED: The Untold Story (DVD)

Be sure to visit the website for more great options!

Make up a basket of your favorite varieties to share or select one of SESE’s mixes like the Virginia Heritage Seed Collection, Welcom-to-the-Garden Pollinator Collection, or the Three Sisters Garden Package. This is a great idea for the adventurous gardener who loves to try new things.

Heirloom loving gardeners will love a seed saving gift basket. Pick out some of your favorite heirloom and open pollinated seed varieties and a few of SESE’s seed saving supplies. Things like self-sealing seed packets or seed vials and seed cleaning screens may not seem exciting to everyone but will make a big difference in the life of your favorite seed saver.

Fertility

It sounds super wierd but anything that will make a garden more productive will make your gardener happier. Gift your friend a homemade compost tea kit, cover crop seeds from SESE, or a garden amendment like work castings or liquid kelp.

If you’ve got a particulary picky friend or just can’t decide what to get consider an SESE gift certificate. You can purchase paper gift certificates or digital ones and leave the tough decisions up to them.

Cold Frame

If you’re into handmade gifts, a coldframe is a simple project for those with basic carpentry skills. For the best effect pair it with some cold hardy seeds or a helpful book like Eliot Coleman’s Four Season Harvest.

Your Seed Collections

Part of Southern Exposure’s mission is to keep varieties alive, so we love seeing others share seeds. If you’re a seed saver consider packaging and gifting some of your own seed collections. This is an especially budget friendly gift idea as well, but another gardener will know just how much you care.

Your Time

Not everyone can go on a shopping spree for their favorite gardener. If your budget is tight consider giving a handmade redeemable coupon for your time. Maybe you could offer 1 hour of weeding or help with springtime planting. There isn’t a gardener in the world that’s not going to be excited about getting some free help!

Whatever your budget you can find a great gift for any of the gardeners, seed savers, permaculturalists, or homesteaders in your life.

Pin it for later: